Growing Through the Years: How Montessori Child Development Prepares Students for Middle School and Beyond

Growing Through the Years: How Montessori Child Development Prepares Students for Middle School and Beyond

When your child is small, every choice can feel like it echoes into the future. Will they stay curious, or burn out early? Will they speak up for themselves, or wait to be told what to do? When middle school shows up with lockers, shifting friend groups, and heavier homework, a lot of parents quietly wonder if their child is ready.

Montessori child development is built for that long view. It doesn’t treat early childhood as a race, it treats it as the root system. At Sandwich Montessori School, children practice independence in real, everyday ways, then carry those habits into bigger academic and social demands.

This post follows that growth, from the earliest years through elementary, then into the middle school shift, so you can see how the pieces fit together over time.

What Makes Montessori Child Development Different

Montessori doesn’t try to “install” learning the way you install an app. It works more like tending a garden. You don’t pull on a sprout to make it taller, you give it light, water, good soil, and time.

That’s why Montessori follows predictable stages of growth, social, emotional, and thinking skills, without rushing children through a checklist. A 4-year-old isn’t expected to sit still like a 10-year-old. A 9-year-old isn’t treated like they should think like a teenager. The approach matches what children are ready for, and stretches them carefully.

Maria Montessori captured the heart of the method in a single line: “Free the child’s potential, and you will transform him into the world.”

That freedom can sound risky until you see how it’s held. Montessori classrooms are warm, but they’re also organized. Children get real choices, in a space designed for success, with adults who guide instead of control. Over time, montessori child development becomes less about what children can repeat, and more about what they can manage, solve, and contribute.

A helpful way to picture it is learning to ride a bike. Training wheels help at first, but they can’t stay forever. Montessori offers a kind of “inner training wheel” that slowly disappears: routines, clear expectations, purposeful work, and steady respect.

Freedom with clear limits builds self-control

Choice in Montessori isn’t a free-for-all. It’s choice inside a prepared space, with clear boundaries that protect safety, focus, and kindness.

Children learn to pick work, stick with it, put it away, and try again when it’s hard. They also learn how to repair mistakes, like cleaning a spill they made, or returning to a classmate to make things right after a sharp comment.

This is the same muscle middle school demands. Students who can switch classes, manage materials, follow rules, and recover from slip-ups without constant reminders have a calmer start. For more on this balance, see Balancing freedom and rules in Montessori classrooms.

Multi-age communities grow empathy and confidence

In a multi-age classroom, younger children watch older ones write, plan, and solve problems. They learn that “bigger kids” aren’t a mystery, they’re teammates.

Older students practice leadership in small, daily ways. They show a first-year student how to begin, how to clean up, how to keep going when something doesn’t work the first time. Younger children learn the skill of asking for help without shame.

Middle school social life can be intense, but this early practice matters. Children who’ve spent years working with mixed ages tend to handle group projects, peer pressure, and changing friendships with more steadiness, because they’ve already lived in a community where everyone is learning at a different pace.

Building the Foundation in Early Childhood (Ages 0 to 6)

Early childhood in Montessori often looks simple, but it’s not small. It’s the stage where children build the habits they’ll rely on later, when work gets longer and choices carry more weight.

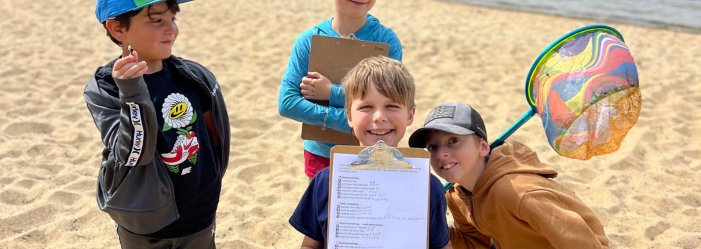

Picture a young child preparing snack. They peel a banana, slice it carefully, place it on a small plate, and wipe the table when they’re done. Another child notices a spill, gets a cloth, and cleans it without drama. Someone else waters a plant and turns the pot toward the light.

These moments can look like “just life,” and that’s the point. Children are practicing attention, order, and care. They’re learning, in their bodies, that they can do real things.

In Montessori, this isn’t framed as chores for the sake of obedience. It’s presented as meaningful work that helps the classroom run. Over time, children start to carry themselves differently. Their pride isn’t loud, it’s calm. It shows up in how they move, how they speak, and how they approach a challenge.

Independence starts with everyday tasks

Practical life activities teach skills that last because they’re useful right now. A child who can pour water without spilling has learned more than pouring.

They’ve practiced:

Focus: keeping attention on a task from start to finish.

Order: following steps in a sequence, then restoring the space.

Coordination: controlling hands, grip, and movement with care.

Pride: the quiet satisfaction of “I did it myself.”

That focus becomes academic stamina later. A child who has spent years finishing purposeful work is less rattled by a longer writing assignment in fifth grade, or a multi-step math problem that doesn’t come quickly.

Responsibility also starts early. When children tidy their space, care for classroom materials, and help maintain a peaceful room, they learn a simple truth: belonging comes with contribution.

Hands-on learning makes reading and math feel real

Montessori doesn’t ask young children to live in abstraction. It gives them ideas they can touch, move, and test.

A child traces sandpaper letters and connects sound to symbol through their fingertips. Another child works with number rods, feeling the difference between “three” and “seven” as length, not as a worksheet answer. The senses support memory, and memory supports confidence.

This matters later when school becomes more abstract. Fractions, essays, and multi-step problem-solving all ask children to hold ideas in their minds. Montessori helps them build that ability gradually, starting with experiences that feel solid and true.

When reading and math begin with the hands, children often approach later challenges with less fear. They’ve learned that confusing ideas can become clear through practice, not through guessing what the teacher wants.

Elementary Years (Ages 6 to 12): Big Ideas, Strong Character

Elementary children want meaning. They notice fairness. They ask bigger questions, and they don’t accept flimsy answers.

Montessori meets this stage with wide, story-rich lessons that connect subjects instead of isolating them. History, science, geography, and art don’t feel like separate boxes. They feel like parts of one world, and the child is invited to explore it.

Just as important, elementary classrooms protect deep focus. Long work periods give children time to settle in, think, revise, and complete what they start. That rhythm is a quiet gift in a world full of interruptions.

If you’re curious how that structure often looks day to day, How Montessori structures the elementary day offers a clear picture.

From concrete to abstract thinking through stories and projects

Montessori elementary learning often begins with big stories, then turns into research and projects. A lesson on the water cycle might lead to a child building a simple model, labeling evaporation and condensation, then writing a short explanation in their own words.

Over time, students practice skills that middle school will assume they already have:

They plan what to do first, and what can wait.

They take notes, not just copy text.

They learn to check sources and ask, “Does this make sense?”

They present their work, even when they’re nervous.

These experiences help children trust their own thinking. Middle school doesn’t only test what students know, it tests how they organize knowledge. Montessori gives them practice before the stakes feel high.

Leadership and teamwork grow in a multi-age classroom

In Montessori elementary, leadership isn’t a title. It’s a daily habit.

Older students help younger ones find materials, explain directions, and stay with a task long enough to finish. That mentoring builds clear speech and patience, because teaching requires both. It also builds confidence that isn’t based on popularity. It’s based on usefulness.

Younger students benefit, too. They see what “capable” looks like up close. They learn that strong students aren’t just fast, they’re steady. When it’s their turn to be the older child, they step into that role naturally.

Middle school brings group work, clubs, and more direct conversations with teachers. Children who are used to collaborating, negotiating roles, and speaking respectfully tend to participate more. They don’t wait on the sidelines as often, because they’ve had years of practice contributing to a community.

Middle School Readiness and the Long-Term Payoff

Middle school can feel like a sudden weather change. One day your child is in a familiar room, the next they’re tracking assignments across subjects, moving through busier hallways, and reading social cues that shift by the week.

Montessori doesn’t promise a stress-free transition. It promises preparation that runs deeper than grades. Because montessori child development is about building internal tools, students often meet the middle school jump with more balance: they know how to start work, how to keep going, and how to recover when something goes off track.

Maria Montessori put it this way: “Education is not something which the teacher does, but a natural process which develops spontaneously in the human being.”

That idea becomes visible in middle school readiness. The payoff isn’t just higher scores, it’s a student who can carry more of the load without losing themselves.

Skills that transfer: time management, focus, and self-advocacy

By the end of elementary, Montessori students have usually spent years setting goals and tracking their work. They learn to see time as something they can shape, not something that happens to them.

In middle school, that looks like:

A student breaks a long-term project into smaller steps, then works a little each day.

They keep track of materials because they’ve been responsible for them before.

They ask a teacher for clarity instead of silently falling behind.

They reflect on progress, then adjust.

Picture a middle school lab report. There’s a question to answer, materials to manage, steps to follow, and a conclusion to write. Students who’ve practiced sustained work and careful sequencing are less likely to panic halfway through. They’ve already learned how to slow down, reread directions, and fix mistakes without spiraling.

Self-advocacy matters just as much. Middle school teachers can’t read every child’s mind. Students need the courage to say, “I don’t understand,” or “Can you check if I’m on the right track?” Montessori builds that courage by treating children as capable partners in their own learning.

How families can support Montessori growth at home

Home doesn’t need to copy a classroom to support Montessori growth. Small routines can protect independence and calm.

Pack lunch together: let your child handle simple parts (containers, fruit, napkin).

Let them choose clothes the night before: fewer morning battles, more ownership.

Give one real household job: set the table, feed a pet, water a plant.

Create a calm homework spot: same place, simple supplies, fewer distractions.

Offer limited choices: “Do you want to start with math or reading?”

Ask one nightly reflection question: “What felt tricky today, and what helped?”

These steps look modest, but they send a strong message: you’re trusted, you’re learning, and you can handle more than you think.

Conclusion

Picture your child on the first day of middle school. The building is bigger, the expectations are higher, and the social world feels louder. Now picture them walking in anyway, steady, curious, and ready to try.

That’s the long arc of montessori child development. It’s not only about what a child knows, it’s about who they become while they’re learning: capable, thoughtful, and able to direct their own effort.

If you’re exploring what this path could look like for your family, learn more about Sandwich Montessori School and the kind of growth that can carry students through middle school and beyond. What would change for your child if school didn’t just push them forward, but helped them build from the inside out?