Building a Kinder, Braver, Stronger Generation: The Character Outcomes of Montessori Philosophy

Building a Kinder, Braver, Stronger Generation: The Character Outcomes of Montessori Philosophy

Parents often picture school as a ladder of skills, reading levels, math facts, grades on a report card. Those things matter, but they’re not what carries a child through a hard friendship, a tough coach, a confusing homework page, or a day when everything feels off.

What carries them is character. The steady kind that shows up when no one is watching.

In a Montessori classroom, you can see it in small, ordinary moments. A child holds the door so a younger classmate can pass with a tray. Another pauses, takes a breath, and waits for a turn instead of grabbing. Someone spills water, then reaches for a sponge and quietly makes it right. That’s the montessori philosophy at work, not as a speech, but as a rhythm.

Maria Montessori believed education should shape the whole child, heart, mind, and hands. This is how Montessori helps children become kinder, braver, and stronger through everyday habits, practiced until they feel natural.

What the Montessori Philosophy Really Means (Beyond the Materials)

People notice the beautiful materials first, the wooden letters, bead chains, tiny pitchers, and maps. But Montessori isn’t a set of objects. It’s a way of treating children, and a way of building a classroom that invites them to grow up from the inside out.

In plain language, Montessori rests on a few simple ideas:

- Children deserve respect, even when they’re still learning.

- Independence is learned by doing, not by being told.

- Choice matters, but it lives inside clear, steady limits.

- Adults can trust children, and children rise to that trust.

Maria Montessori captured this trust with a line that still stops many adults in their tracks: “The greatest sign of success for a teacher is to be able to say, ‘The children are now working as if I did not exist.’”

That doesn’t mean adults disappear. It means the child becomes the main worker, the main thinker, the main doer.

In a typical teacher-led classroom, the day often moves to an adult’s drumbeat. The teacher chooses the lesson, the pace, the next step, and the definition of “done.” Montessori looks different in ways you can feel:

- Student choice: children choose work from options they’ve been shown, then repeat it until they’re satisfied.

- Mixed ages: younger children learn by watching, older children learn by leading, and community becomes real.

- Long work periods: time stretches, so focus can deepen instead of being chopped into quick rotations.

- Self-correcting materials: many works show the child when something is off, so feedback doesn’t always come from an adult.

The goal isn’t just smart kids. It’s capable, caring people. If you want a broader picture of how Montessori supports the whole child, including social and emotional growth, Understanding Montessori's focus on holistic growth can help.

The classroom is designed for self-control, not constant adult control

A Montessori room teaches quietly. Shelves are tidy and open. Materials are placed with intention. Tools fit small hands.

There’s usually one of each work, which sounds simple, but it changes everything. If a child wants the pink tower and it’s in use, they can’t demand it. They wait, choose something else, or ask for a turn. Patience stops being a lecture and becomes a daily practice.

Routines are calm and predictable. Work is carried carefully, used with care, returned to its place. The room sends a steady message: you belong here, and your choices matter.

The guide teaches by observing and modeling, not by hovering

Montessori teachers are often called guides for a reason. Their work starts with watching, not talking.

A guide notices what a child is drawn to, what they avoid, where they hesitate, and when they’re ready for the next challenge. Then the guide invites, demonstrates, and steps back. Help is offered like a handrail, not a takeover.

When conflict pops up, the guide coaches children toward words, turn-taking, and repair. Over time, children learn they can handle problems with support, not rescue. That builds trust in the classroom, and it builds confidence in parents too.

Kinder, Braver, Stronger: The Character Outcomes Montessori Builds Every Day

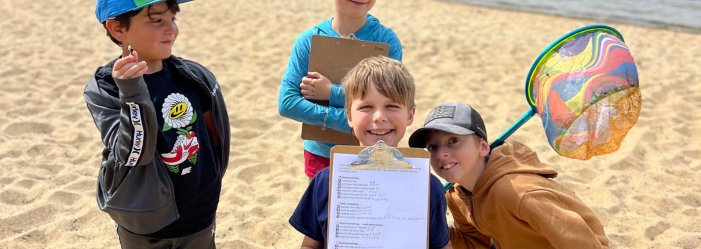

Picture a morning work cycle. The room hums instead of buzzes. You might hear a soft “excuse me,” the gentle scrape of a chair pushed in, a whisper of a broom. Children move with purpose, like they have somewhere important to be, because they do.

A child chooses a tray with pouring work. Another unrolls a rug, smoothing the corners like they’re making a small stage. Across the room, an older child points to a line of words, helping a younger one match sounds without grabbing the cards.

Nobody is handing out gold stars for this. That’s the point. These traits are practiced in the smallest moments, then repeated day after day until they stick.

There’s a Montessori line that fits this daily practice: “Never help a child with a task at which he feels he can succeed.” It’s not about being hands-off. It’s about protecting the child’s belief that, with effort, they can do hard things.

Kindness grows from respect, grace, and daily community life

Montessori kindness doesn’t start with “be nice.” It starts with respect, taught in ways children can actually use.

Grace and courtesy lessons are short, concrete, and practiced like any other skill. A guide might show how to greet a friend, how to offer help, how to interrupt politely, how to wait, how to carry something without bumping into others. Then children try it in real life, when it counts.

You’ll often see older children support younger ones, not because they were told to, but because the classroom is built for it. A 5-year-old shows a 3-year-old how to roll a rug from the edge, keeping it tight. A child demonstrates how to carry a tray with two hands, slow and level, like carrying something precious. The younger child watches, then tries, then tries again.

Kindness also shows up in care for the space. Children water plants, wipe tables, sweep crumbs, and return work to the shelf so someone else can find it. This isn’t “classroom chores” as punishment. It’s shared life.

When children learn to notice a drooping leaf or a spill near someone’s feet, they’re learning empathy in a practical form. They’re learning to look outward, not just inward.

Bravery shows up when children choose hard work and try again

Bravery in Montessori doesn’t mean being loud or fearless. It means choosing the work that stretches you, then staying with it.

A young child pours water from a tiny pitcher into a glass. Their hand wobbles. The water line rises. A drop slips over the rim. Nobody gasps. Nobody rushes in. The child gets a sponge, wipes the tray, and pours again. The room treats mistakes like weather, expected and manageable.

Later, that same child may tackle button frames, zippers, or shoe-tying. Each task says, you can do things for yourself. That kind of bravery has a quiet sound. It’s the sound of persistence.

As children grow, bravery takes new forms. An elementary-age student might share a project with classmates, reading aloud even with a shaky voice. A small group might try to solve a real problem, how to divide roles fairly, how to test an idea, how to handle disagreement without blowing up.

Bravery also includes speaking up with respect. “I don’t like that,” said calmly. “Can I have a turn when you’re done?” “Please stop.” These are strong words, and Montessori gives children a place to practice them.

Strength is self-discipline, focus, and bouncing back after mistakes

Strength is often mistaken for toughness. In Montessori, strength looks more like self-control.

Freedom exists, but it’s not a free-for-all. Children choose their work, but they’re expected to use it with care, finish the cycle, and restore the space. That simple arc, choose, do, complete, return, builds self-discipline without nagging.

Long work periods matter here. When children aren’t rushed from station to station, they can settle. They might repeat a work again and again, not for a grade, but for mastery. Focus becomes something they own.

Conflict is part of the training too. Two children want the same work. One says, “I’m using it.” The other feels the flare of frustration, then uses the tools they’ve practiced. They ask for a turn. They watch for an opening. They choose another work and come back later. Sometimes a guide helps them put words to the feeling. Often, they can handle it themselves.

This is strength with a steady pulse, calm problem-solving, patience, and the ability to begin again without drama.

Why Montessori Character Lessons Last Into the Teen Years and Beyond

It’s easy to admire these traits in the early years, then wonder if they’ll hold when life gets more complicated. Middle school brings social pressure. Sports bring wins and losses. Teens meet harder math, heavier feelings, and bigger mistakes.

Montessori character lessons often last because they aren’t taught as slogans. They’re built into daily life, like muscle memory.

Many studies suggest Montessori students often show stronger self-regulation, social skills, and motivation. Results vary by program and child, but the pattern makes sense. When children practice managing themselves every day, they carry that skill into other settings.

At home, parents often notice changes that look small, but feel huge:

- A child starts a task without being chased.

- Frustration shows up, but it doesn’t take over the whole room.

- Siblings have more moments of kindness, even if they still squabble.

Academics matter, but character protects learning when things get hard. A child who can steady themselves can keep going.

If you’re curious how different age levels support these habits over time, Montessori programs fostering independence and kindness offers a helpful overview.

A child who can manage themselves can learn anything

Self-management is the hidden engine behind school success. Planning, finishing, and handling feelings are what make learning possible on a rough day.

When those skills grow, parents may see simple signs:

A child sticks with a puzzle longer, even when it’s annoying. They clean up a snack without being asked, because the habit is built in. They ask for help with words instead of melting down, because they’ve learned that problems can be named and solved.

These aren’t perfect behaviors. They’re steady progress.

A child who can live in community becomes a strong citizen

Mixed-age classrooms teach children that community isn’t theoretical. It’s daily life with real people who have different needs.

Older children learn leadership that isn’t bossy. Younger children learn that help can be kind, not controlling. Everyone learns that fairness doesn’t always mean “same.” It means paying attention and doing what’s right.

Later, those lessons show up in group projects, sports teams, part-time jobs, and family life. A teen who can take feedback without falling apart has a real advantage. A young adult who can disagree without disrespect can build strong relationships.

Montessori doesn’t just prepare children to succeed. It prepares them to belong, and to contribute.

Conclusion

If school only builds academics, it leaves kids unguarded for the harder parts of life. Education is also about who a child becomes when no one is grading them.

Montessori aims for that deeper growth, shaping children who are kinder, braver, and stronger in ways you can see in ordinary days, how they speak, how they work, how they recover, how they treat others.

The best part is how quietly it happens. A spilled cup becomes practice. A shared lesson becomes leadership. A long work cycle becomes focus that lasts.

Maria Montessori said it clearly: “The child is both a hope and a promise for mankind.” If you’re considering Montessori, observe a classroom, talk with a guide, and notice the small moments. They’re building something big.

Book a tour at Sandwich Montessori School today to learn more.